This year’s presidential debates in the United States were not without controversy and Craig LaMay, professor and acting director of the Journalism and Strategic Communication Program, is in a unique position to discuss them as the co-author of a book about the debates’ history and legal controversies surrounding them.

LaMay, who has been involved with television and elections around the world for almost 30 years, is quick to dispute accusations of partisanship that have been leveled against the U.S. Commission on Presidential Debates, pointing out that the organization is required by law to be both non-profit and non-partisan. The Commission, which succeeded the League of Women Voters, has sponsored the debates since 1988 and sought to put them on a better footing.

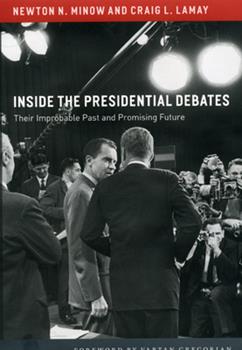

LaMay’s association with the Commission began through his writing partnership with former FCC Chairman and the Commission’s founder, Newton Minow, who LaMay says is “the only person who’s been involved in every presidential debate since the very first one in 1960.” LaMay and Minow’s 2008 book about the debates, from the University of Chicago Press, chronicles the development of the debates under U.S. communications, First Amendment and election law, but also as a story about the twists of modern electoral politics. After all, LaMay, says, “the candidates don’t have to debate and have sometimes chosen not to.”

While the bulk of his work on leader debates has been working with other countries on technical questions about “who gets to participate and on what terms,” LaMay was also privy to in this year’s debates between Donald Trump and Joe Biden through his collaboration with Minow.

Following the criticism the Commission received after the first debate -- that Trump had interrupted the moderator, Chris Wallace, and Biden too frequently and news outlets editorialized “that the debates should just be ended for all times” -- LaMay said that the mute button was introduced for the third debate (after the second was canceled). According to LaMay, this decision received mixed reviews but ultimately satisfied the more critical goal of serving voters.

“It wasn’t done because there was a view that one candidate or the other needed to be controlled; it was done because this is a public service,” LaMay said, explaining that the Commission’s first duty is to the voting and viewing public, “and so if a muting button for the first two minutes of a section allowed at least an introduction of a topic, then that served the voter.”

Through his work on the U.S. presidential debates with Minow and with broadcast journalists and policymakers in other countries, LaMay made a number of observations about the US presidential debates, the first being that they have become “de facto mandatory.”

While candidates are not obligated to participate in these debates, LaMay said, they “can’t back out any longer without demeaning themselves in front of their own supporters.” President Trump’s refusal to do a second virtual debate this year was the first time a candidate had missed a debate since 1980 when President Carter skipped that year’s first debate with Ronald Reagan and third-party candidate John Anderson. Still, LaMay said, the debates “have become an institution, and there are many reasons for this, but we (the U.S.) have had uninterrupted debates since 1976. The public expects them.”

He also observed that while “nobody in the world admires the way the Americans do their presidential elections,” in part because they carry on for too long, cost too much, and are too heavy on advertising, the presidential debates, by contrast, are the most genuine moment in the modern presidential campaign.

“It’s the only place in the entire process where you get to see the two candidates speaking at length, and extemporaneously, to each other and to the public, without notes, without benefit of their minders standing there, and the American people can watch the candidates and judge them for themselves as to their character, their ability to handle themselves and to think on their feet,” LaMay said.

These qualities, LaMay added, speak not only to the “great success of the Commission,” but also to the way in which it has contributed to making the debates an international institution. “I think that debates are important for that reason alone,” he said. “They’re a normative exercise in democracy that more than a hundred countries now emulate.”

LaMay, who teaches communications law at Northwestern in both Evanston and Doha, said that these themes also cross over into his classroom, especially as concerns countries in transition. Any democracy, he said, must ultimately confront the “threshold question of how you use television and radio as tools of political campaigning and political communication.”